Like Matthew’s account of Jesus’ birth, the coming of the Magi reveals who understands Christmas. But like a magic trick, we get so caught up in what is right before us. Because we are distracted, we miss the bigger picture.

Whose Story is This?

Growing up, the basic lesson of Epiphany, the January 6 celebration of the Magi coming to Jesus, focused on Jesus being the savior of the Gentiles (non-Jews), too. But how did the Magi find themselves in this story?

There are an array of theories out there. Some figure that the Magi had a copy of ancient Jewish scrolls that they studied. This seems skeptical at best. Matthew quotes the Hebrew Bible right and left. But when it comes to the Magi, he makes no mention of the text that compelled them to journey West.

Others hypothesize that the Magi follow in the footsteps of Daniel (from lion den’s fame). Daniel was a Hebrew boy taken off to Babylon who rose to significance because of his ability to interpret dreams. He held a powerful role in Babylon during the reigns of Darius and Nebuchadnezzar. This theory assumes others followed in his footsteps. Then it wants us to believe the conquering Persians allowed those closest to the Babylonian king to survive. That strikes me as rather unlikely.

Another suggests that they are part of the tribe of Levi, one of the twelve tribes of Israel. But this undermines the central message we started with, that Jesus is for both Jews and Gentiles.

The major problem with these approaches is their attempt to shoehorn the Magi into the existing Biblical narrative. They assume the Bible must hold the entirety of God’s story as it relates to humanity.

This view of the Bible is the same kind of thinking that prompts some to make Genesis a science book.

God Beyond the Bible

But the Bible itself makes it clear that God is active with the creation beyond its pages. We see this in the story of Job whose is in the Bible, but disconnected from the primary narrative. It is also there in the story of Melchizedek the king of Salem and priest of the “Most High God.”

For those unfamiliar, as the primary narrative develops, Melchizedek shows up in Genesis 14 and blesses Abraham. Then in Hebrews, Jesus is described as a priest in the order of Melchizedek. The only way to understand Melchizedek is to have God operating in multiple narratives. Occasionally the Bible bears witness to how those different narratives bump into one another. We see the same thing with Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses and the High Priest of Midian.

So if God has other narratives running with Job, Melchizedek, and Jethro, and foreigners like Rahab and Ruth were faithful before hearing of God’s promise to Abraham, then why do we need to somehow tie the Magi into the narrative we are most familiar with?

My guess, the Magi were astrologers and Western Christianity equates that with the occult. Never mind that Matthew says they followed the stars. Skip over the long Biblical history of the divine voice speaking through animals or signs or dreams. Ignore that even today a Muslim Bedouin tribe in Jordan calls themselves the al-Kaokabani (those who study and follow the planets) because their ancestors journeyed west to worship the newborn Jesus. As soon as the Bible threatens the narrative, we try to save the narrative and change the Bible.

Yet the magic of the Magi is their invitation to believe that God operates in more ways than we can imagine. Yes this means faith is less about cognitive ascent to a certain set of historical facts. Belief is about embracing a diving invitation to a different way of life. The goal is not to figure out who is in and who is out. Instead we need to spend time asking how storylines might intersect and inform one another.

Walls or Wells?

Years ago I read Anthropological Reflections on Missiological Issues. In it, the author introduced me to the idea of bounded and centered sets.

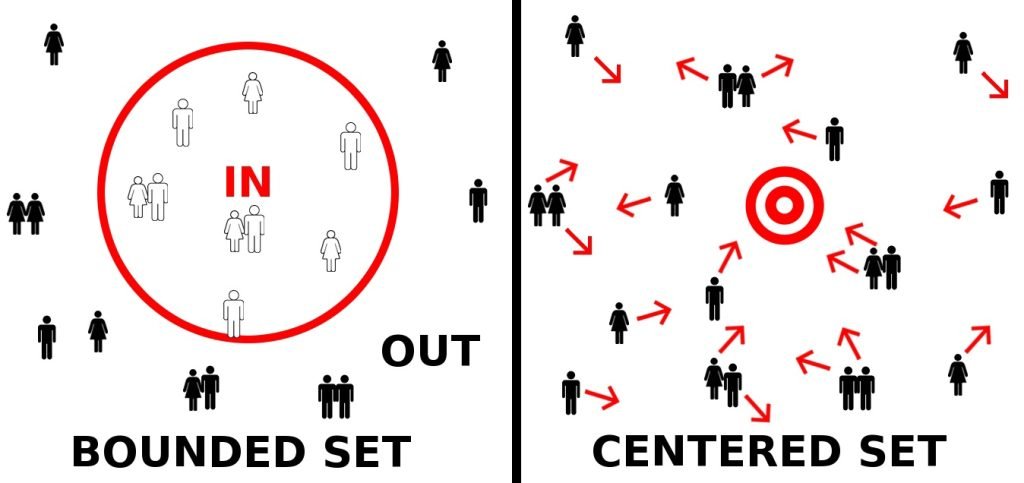

A bounded set is a wall. It determines who is in and who is out. In contrast, a centered set focuses not on location, but direction. It asks whether you are moving towards or away from the divine invitation. In this image, God sets up a well (or wells) where we can drink life-giving water. The question is whether or not we hear the invitation to approach the well and drink.

By ancient Jewish standards, the Magi were outside the wall. They were Gentiles or, more crassly, goy. They lacked both the history and the heritage that would grant them access to the King of the Jews. And yet, here they come. Why? Because Jesus is not about walls but inviting everyone to drink from the well that gives life. God used the stars to invite the Magi to come and drink from the well.

To put it another way, it is not about the story we embrace but the spirit. Faith is about learning to abandon a spirit of power and embrace one of love.

This does not mean all religions are the same. It does call us to ponder whether we can find the same faith within different religions.

Religion vs. Spirituality

Another way to think about all this stems from the world of spirits, as in distilled adult beverages.

Over the years I have tasted cheap and well-crafted variations of whiskey, tequila, and rum. While it was single malt scotch whisky that first taught my palate to appreciate the nuance of a finely distilled beverage, the appreciation extended to other drinks. Finally, a few years ago while visiting Cuba, I made the connection.

If you taste both basic and finely made whiskeys, tequilas, and rums, you notice the basic variations are very different. However, the finer versions have complexities that create greater commonality with each other than their cheaply made counterparts.

The same is true of world-class cities. New York, Berlin, London, and Tokyo have more in common with each other than they do other cities just a few hundred miles away.

Could Christmas Magi(c) invite us to realize that those who discover a spirit of love, no matter the path they took to get there, have more in common with each other than they do with those creating division as they seek to gain power over others?

Further Exploration

Book: Love Poems From God: Twelve Sacred Voices from the East and West by Daniel Ladinsky

Mystics and poets from the Christian, Sufi, and Jewish traditions are brought together in this book. When you read the poems, I doubt most readers could identify the tradition each author comes from.

Book: The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope For, and Believe by Richard Rohr

If God sets up wells for us to drink from, the Richard Rohr would argue that the Christ who put on flesh is the aquifer that feeds them all.

Action

Find something from outside of your own faith tradition. I could be a poem, a sunset, a story, or a star. How might this be an opportunity to worship the divine?

What’s Next?

As we head into a new year, let’s explore what’s next for Abundance Reconstructed.